What does detox mean to you? For many, the word detox brings up images of restrictive diets where drinking nothing but lemon juice for a week somehow translates into enhanced wellness.

In reality, detoxification is not a wellness trend. It’s a physiological process that runs behind the scenes in your body every single day. When it’s working well, you feel great, but sometimes due to lifestyle or illness, the process can fall out of balance.

Supporting detoxification requires a holistic approach that includes multiple diet and lifestyle factors. Still, certain foods and supplements, especially those found in cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, can help bring the body back into equilibrium. Sulforaphane and Diindolylmethane (DIM) are two phytochemicals found in cruciferous veggies that can be powerful tools for optimising the body’s already impressive detoxification system.

How does your body detox?

Every day you come into contact with potentially harmful compounds from the outside world via your skin, lungs, and GI tract. You also create toxic byproducts as a normal part of metabolism (think free radicals). Detoxification is the process by which your body neutralises and removes these products, so they don’t cause any damage or detrimental health effects.1

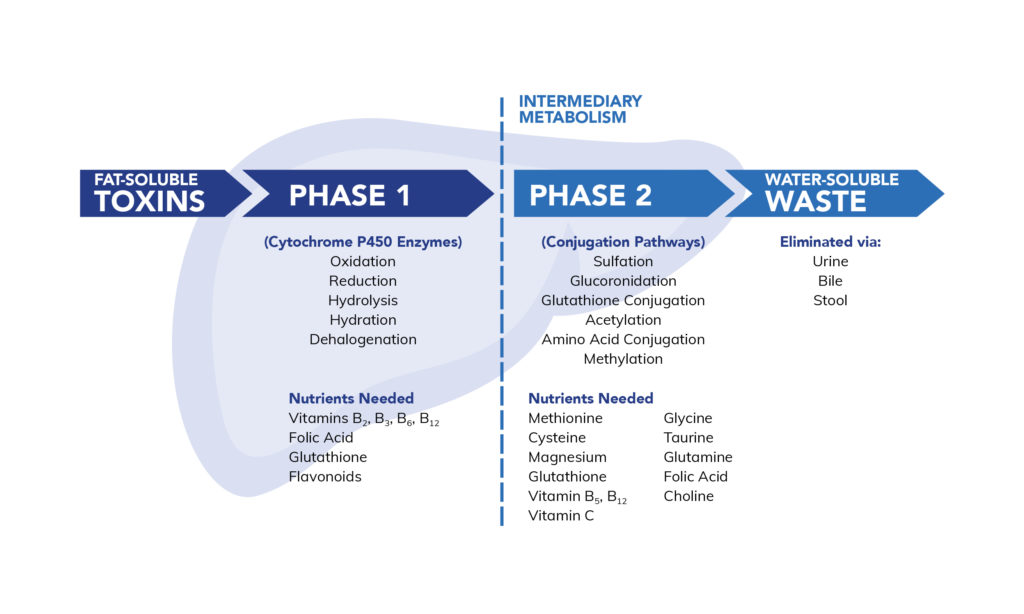

Your liver is the primary organ involved in detoxication, but other organs also play an essential role in the process, including your GI tract, kidney, lungs, skin, and lymphatic system.2 Anything potentially toxic to the body goes through several steps before being eliminated from the body, broken down into three phases:

- Phase one: Toxins or drugs are converted into intermediate water-soluble compounds that are easier to remove from the body. Often the compounds created in this phase are even more toxic, but it’s a necessary step before they are conjugated in phase two.

- Phase two: Phase two transforms the intermediates from phase one into water-soluble compounds that are safer and easier to excrete.

- Phase three: Phase three transports the final water-soluble products out of the body via urine, stool, sweat, and breath.

When you break down the individual phases of detoxification, it helps to understand how important the balance between them truly is. Without an efficient phase two, phase one products can bottleneck and cause problems. Movement out of the body in phase three is equally important as without excretion, you can’t get rid of the byproducts. You can’t simply focus on phase one without balancing phase two or vice versa, as imbalances can lead to health concerns, including oxidative stress, gut health disruptions, hormone imbalances, and more.3

How do cruciferous vegetables support detoxification?

Cruciferous vegetables (also known as the brassica family of veggies) contain two important glucosinolates (unique sulfur-containing compounds) that impact detoxification: sulforaphane and DIM.

Sulforaphane

Sulforaphane is a natural sulfur-containing compound found in cruciferous veggies, especially broccoli, that is well studied for its health benefits, including acting as an antioxidant and supporting healthy inflammatory responses.4 Sulforaphane promotes healthy detoxification balance through its actions on phase one and two detoxification pathways.5

Studies tell us that sulforaphane plays a role in inhibiting the overproduction of intermediates in phase one while turning up the transformation process in phase two.6 This is especially important as research suggests an overaccumulation of toxic byproducts of phase one without an equally balanced phase two activity can seriously impact your health.7 Sulforaphane appears to help balance this process by promoting cell regulation and inflammation reduction while also supporting liver function.8,9,10

Sulforaphane also promotes the upregulation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Nrf2 is a transcription factor activated in response to oxidative stress. It supports the expression of hundreds of genes involved in detoxification (especially phase two enzymes) and cellular antioxidant protection.11

DIM

DIM also comes from brassica vegetables as a metabolite from indole-3-carbinol (I3C). During digestion, I3C, an unstable compound, is converted to DIM in response to the acid in your stomach.12 DIM is a much more stable metabolite and also supports the body’s detoxification pathways.

Studies suggest that DIM can promote the upregulation of genes that control the expression of your detoxification enzymes. It also supports a healthy inflammation balance in the body. DIM supplementation may be especially supportive for the detoxification of women’s hormones, especially oestrogen. DIM supports a healthy balance of oestrogen metabolism, shifting the ratio in favour of the more protective forms.13

Which veggies are high in sulforaphane and DIM?

The cruciferous vegetables include:

- Broccoli and broccoli sprouts

- Cabbage

- Brussels sprouts

- Kale

- Cauliflower

- Bok choy

- Collard greens

The way you prepare these veggies affects how much of these compounds you absorb. Heating increases absorption, but overdoing it can also inhibit bioavailability. Based on research on broccoli, steaming is the best way to obtain sulforaphane14

While it’s always ideal to obtain these phytonutrients from the sources listed above, you may need a higher amount of DIM or sulforaphane to impact a specific health concern. In this case, supplement options can be a way to get a higher amount as a compliment to your food sources.15

Both sulforaphane and DIM supplements are available in a variety of forms, from powders to capsules, but should ideally be directed by a health care practitioner to make sure you are getting the proper form and dosage for your individual needs.

Using cruciferous vegetables for detox support

It’s well accepted that broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables are good for you, and their role in detoxification may be a reason why. Including a few servings each day of these powerful phytochemicals is a smart way to optimise your health and support all phases of detoxification. DIM or sulforaphane supplements may also provide added value to help bring all phases of detoxification into balance.

1. Raunio, Hannu, Mira Kuusisto, Risto O. Juvonen, and Olli T. Pentikäinen. “Modeling of Interactions between Xenobiotics and Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Enzymes.” Frontiers in Pharmacology 6 (June 12, 2015). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2015.00123.

2. Chiang, J. “Liver Physiology: Metabolism and Detoxification.” In Pathobiology of Human Disease, edited by Linda M. McManus and Richard N. Mitchell, 1770–82. San Diego: Academic Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386456-7.04202-7.

3. Orešič, Matej, Aidan McGlinchey, Craig E. Wheelock, and Tuulia Hyötyläinen. “Metabolic Signatures of the Exposome-Quantifying the Impact of Exposure to Environmental Chemicals on Human Health.” Metabolites 10, no. 11 (November 10, 2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10110454.

4. Kim, Jae Kwang, and Sang Un Park. “Current Potential Health Benefits of Sulforaphane.” EXCLI Journal 15 (October 13, 2016): 571–77. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2016-485.

5. Egner, Patricia A., Jian-Guo Chen, Adam T. Zarth, Derek K. Ng, Jin-Bing Wang, Kevin H. Kensler, Lisa P. Jacobson, et al. “Rapid and Sustainable Detoxication of Airborne Pollutants by Broccoli Sprout Beverage: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial in China.” Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia, Pa.) 7, no. 8 (August 2014): 813–23. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0103.

6. Riedl, Marc A., Andrew Saxon, and David Diaz-Sanchez. “Oral Sulforaphane Increases Phase II Antioxidant Enzymes in the Human Upper Airway.” Clinical Immunology (Orlando, Fla.) 130, no. 3 (March 2009): 244–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2008.10.007.

7. Kim, Jae Kwang, and Sang Un Park. “Current Potential Health Benefits of Sulforaphane.” EXCLI Journal 15 (October 13, 2016): 571–77. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2016-485.

8. Yang, Li, Dushani L. Palliyaguru, and Thomas W. Kensler. Seminars in Oncology 43, no. 1 (February 2016): 146–53. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.09.013.

9. Kikuchi, Masahiro, Yusuke Ushida, Hirokazu Shiozawa, Rumiko Umeda, Kota Tsuruya, Yudai Aoki, Hiroyuki Suganuma, and Yasuhiro Nishizaki. “Sulforaphane-Rich Broccoli Sprout Extract Improves Hepatic Abnormalities in Male Subjects.” World Journal of Gastroenterology 21, no. 43 (November 21, 2015): 12457–67. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12457.

10. Tortorella, Stephanie M., Simon G. Royce, Paul V. Licciardi, and Tom C. Karagiannis. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 22, no. 16 (June 1, 2015): 1382–1424. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2014.6097.

11. Santín-Márquez, Roberto, Adriana Alarcón-Aguilar, Norma Edith López-Diazguerrero, Niki Chondrogianni, and Mina Königsberg. “Sulforaphane – Role in Aging and Neurodegeneration.” GeroScience 41, no. 5 (October 2019): 655–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-019-00061-7.

12. Licznerska, Barbara, and Wanda Baer-Dubowska. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 928 (2016): 131–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41334-1_6.

13. “Nutrition Reviews | Oxford Academic.” Accessed March 30, 2021. https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/74/7/432/1752161.

14. Wang, Grace C., Mark Farnham, and Elizabeth H. Jeffery. “Impact of Thermal Processing on Sulforaphane Yield from Broccoli ( Brassica Oleracea L. Ssp. Italica).” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 60, no. 27 (July 11, 2012): 6743–48. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf2050284.

15. Fahey, Jed W., W. David Holtzclaw, Scott L. Wehage, Kristina L. Wade, Katherine K. Stephenson, and Paul Talalay. “Sulforaphane Bioavailability from Glucoraphanin-Rich Broccoli: Control by Active Endogenous Myrosinase.” PloS One 10, no. 11 (2015): e0140963. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140963.